Whether you credit him with banishing snakes, bringing Christianity, or giving us a bank holiday weekend, St Patrick’s Day is undoubtedly an excellent chance to celebrate our small country.

But what do we know of the man himself? Where was he born? When was he born? And why do landmarks around the world go green in celebration of him?

Who was Saint Patrick?

Ireland has three official patron saints: Saint Patrick, Saint Brigid, and Saint Columba.

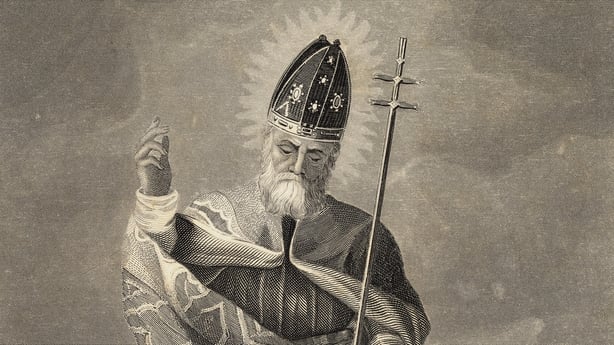

Saint Patrick, also the national apostle of Ireland, is one of Christianity’s most widely known figures and is credited with bringing Christianity to Ireland.

Despite this, much of what we know about him stems from oral myth and legend, meaning that scholars have been left to debate almost every detail of his life.

When was he born?

Depending on what you read, he may have been born Maewyn Succat (but maybe not), in Britain (or Brittany) in 373 (or 390). Suffice to say the details are sketchy.

In fact, what we do know about Saint Patrick stems from just two written sources: his letter to Coroticus, and his autobiography, Confessio.

“My name is Patrick. I am a sinner, a simple country person, and the least of all believers. I am looked down upon by many. My father was Calpornius. He was a deacon; his father was Potitus, a priest, who lived at Bannavem Taburniae. His home was near there, and that is where I was taken prisoner. I was about sixteen at the time.”

How did he come to Ireland?

From his writings, it seems that Saint Patrick was born during Roman times to a wealthy family and was the son of Calpurnius, a deacon and local official.

When he was just 16, he is said to have been kidnapped from his home by Irish raiders before being sold into slavery. He was then brought to Ireland where he was kept as a prisoner and put to work as a shepherd.

It was during this time that he is said to have turned to religion. After six years spent guarding animals on a hillside, he claims that God came to him in a dream and told him that a ship was waiting, and he knew it was the answer to his prayers.

Following the dream, he escaped Ireland and was reunited with his family. However, it wasn’t long before he is said to have another dream, one that showed him visions of the Irish people calling for his return.

Following this, he traveled to France to train in a monastery and dedicated his life to learning before returning to Irish shores with the blessing of the Pope.

We need your consent to load this YouTube contentWe use YouTube to manage extra content that can set cookies on your device and collect data about your activity. Please review their details and accept them to load the content.Manage Preferences

In 2012, Dr. Roy Flechner, a research fellow at Cambridge University’s Department of Anglo-Saxon, Norse, and Celtic (ASNC), claimed that the traditional story of St Patrick was “likely to be fiction”.

Flechner’s study dismisses the story of enslavement and instead argues that Patrick fled Britain deliberately to avoid becoming a Roman tax collector.

“In the troubled era in which Patrick lived, which saw the demise and eventual collapse of Roman government in Britain in 410, discharging the obligations of a Decurion, especially tax collecting, would not only have been difficult but also very risky,” Dr. Flechner said.

Whatever the truth, Saint Patrick is celebrated around the world on 17 March which is believed to be the date he died in 461 A.D (maybe).

Did he really banish all the snakes?

Saint Patrick is often credited with ridding the cold and wet island of Ireland of snakes during the fifth century. Unsurprisingly, this story has been disputed many times over.

Nigel Monaghan, keeper of natural history at the National Museum of Ireland in Dublin, told National Geographic that there were likely no snakes in Ireland in the first place:

“At no time has there ever been any suggestion of snakes in Ireland. There was nothing for St. Patrick to banish.”

Instead, scholars believe the tale to be allegorical as serpents were seen as symbols of evil, and were likely a representation of what Patrick was ridding Ireland of due to his Christian teachings.

Others believe that the snakes may have symbolised Pagan deities as one of the “serpents” that he is supposed to have defeated is the female Caoránach or Keeronagh.

In some accounts, the saint is described as pursuing this creature or “mother of devils” from Croagh Patrick as far as Lough Derg in Co Donegal.

Read more: Was St Patrick a feminist?

What is the meaning of the shamrock?

As many of us will remember from our annual lesson in primary school, the shamrock is said to have been used by Saint Patrick to assist in his teachings of Christianity.

According to legend, Patrick plucked a shamrock from the ground and used the three petals to demonstrate the Trinity: Father, Son, and Holy Spirit.

The shamrock has since become a common symbol of Ireland and is used year-round on flags and logos to indicate a link to the country.

Every year, Ireland’s Taoiseach will present the President of the United States with a bowl of shamrocks at the White House on St Patrick’s day. The custom first began in 1952 when Irish Ambassador John Hearne brought the plant to President Harry Truman as a gift.

As Irish people began to emigrate in great numbers they brought their culture and traditions including Saint Patrick’s Day to every corner of the globe.

Surprisingly, the first-ever parade was actually held in New York City thanks to a band of Irish soldiers who were serving in the British army in the city.

Why does the world go green>

Traditionally, parades take place across both the country and the world with the biggest parade taking place in New York City – a parade that often features around 150,000 participants and attracts more than two million spectators.

Outside of Ireland, the day is also a public holiday on the Caribbean island of Montserrat known as the Emerald Isle of the Caribbean which usually hosts a week-long celebration.

Don’t forget that Seachtain na Gaeilge runs for the first two weeks of March and culminates on Saint Patrick’s Day, making it the perfect excuse to break out your cúpla focal.